In Robert Greene’s seminal book for corporate psychopaths, The 48 Laws of Power, the 48th Law is “Assume Formlessness.” Greene’s law suggests that adopting a fluid and ever-changing state makes it more challenging for others to grasp or control you. In a state of formlessness, you are constantly shifting, hard to pin down, and difficult to predict, giving you a unique kind of power. He asserts this principle can be a transformative approach to achieving personal and professional goals. For me, it is the only useful and well-advised “law” in Greene’s otherwise seriously problematic book which is a kind of neo-Machiavellian handbook for assholes. But what does it mean to truly “assume formlessness”? And how can this concept go beyond mere adaptability to transform how we navigate life’s challenges?

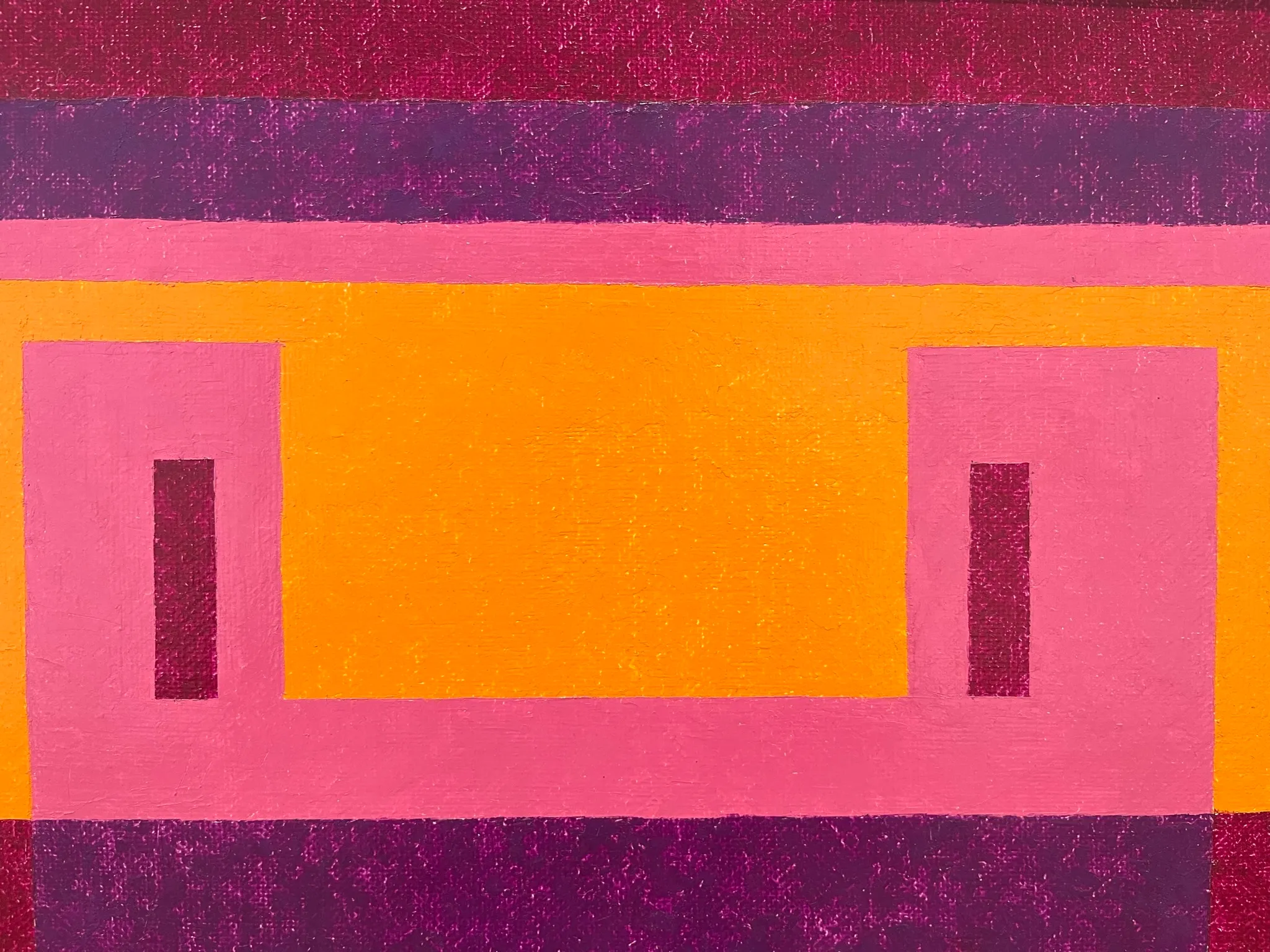

In the book and exhibition *Formless: A User’s Guide* by Yve-Alain Bois and Rosalind E. Krauss, formlessness is explored as a critical concept that challenges traditional structures and hierarchies in art, thought, and life. Bois and Krauss draw upon the work of Georges Bataille to argue that the formless is not a fixed form but an operation—a way of undoing form, structure, and categorization itself. This “undoing” is not a destruction but a freeing from constraints, a radical opening to new possibilities that exist outside conventional boundaries.

Formlessness as an operation aligns with the notion of being adaptable in life, as suggested by the 48th Law. When you strive to achieve your goals, it’s not just about rigidly adhering to one method; it’s about being open to various ways of moving forward. Let’s say hypothetically that recently you’ve faced challenges such as failing to wake up on time—a seemingly small issue that snowballs into a day defined by guilt and shame. However, by adopting a more formless approach, you can stop allowing one minor failure to dictate the rest of your day.

Formless: A User’s Guide argues for a mode of thought and action that refuses to adhere to traditional values, hierarchies, or expectations. Similarly, why should you let an arbitrary metric like waking up at a specific time become a measure of your entire day’s success or your self-worth? It’s crucial to realize that the guilt and shame you feel are constructs—rigid forms imposed by internal or external pressures. By assuming formlessness, you dissolve these forms and liberate yourself, opening to new ways of being productive and fulfilled, feeling in control of your own narrative.

When you stop worrying about perfect timing or doing everything right, you may find new ways to connect with the essential. This is an example of what Bois and Krauss call l’informe, a concept that does not merely describe the absence of form but suggests an active engagement with breaking down forms that constrain thought and action. Rather than seeing your late mornings as failures, you can begin to focus on what is essential, allowing for a kind of productive chaos—a way of reshaping your plans according to the moment’s needs, feeling inspired and creative in your approach.

Bois and Krauss explore several categories of the formless—base materialism, horizontality, pulse, and entropy. Each of these suggests a different way of thinking about dissolving form. For example, *entropy* speaks to the idea of natural disintegration, a process that isn’t about losing order but finding a different kind of structure within apparent disorder. In our hypothetical context, waking up late could be seen as a form of entropy—not a failure, but an opportunity to find a different rhythm that works for you.

By refusing to let guilt dictate your day and making judgment-free adjustments based on your situation, you align yourself with this concept of formlessness. You engage in a kind of *base materialism*—recognizing that the supposed “ideal” forms (like perfect routines) are not superior or necessary. Instead, you find value in the raw, unpolished materials of your life and goals.

Formlessness, then, is not about the absence of structure but is instead about a refusal to be limited by preconceived structures. It’s about maintaining a stance of openness, where adaptability is not a compromise but a strategy for living authentically and truthfully. By moving through the world this way you are not beholden to rigid forms or routines; you’re capable of creating and recreating the frameworks that suit you best, feeling liberated and empowered in your choices.

Adopting the principle of formlessness in your daily process means recognizing that setbacks, like waking up late or drinking too much or making any kind of mistake, are minor events that should not carry disproportionate weight. By dissolving the rigid forms of guilt and self-reproach and opening yourself to new, judgment-free possibilities, you can find new ways to achieve your goals. In the spirit of *formlessness*, you liberate yourself from conventional boundaries, embracing the productive potential that lies within the fluid, the adaptable, the formless, and ultimately the essential.

You must be logged in to post a comment.